It is often tragedy, outrage or joy that conspire to force one to write. Writing at it's best is a compulsion, with words pouring out in torrid waves and smashing onto the page. Words can be weapons, far deadlier than any sword, or they can be tools of diplomacy, the well crafted essay shifting the Zeitgeist and molding it as though it were something malleable. Very few writers can be said to truly matter - to have the necessary brain and talent to shift debate. This can be said all the more so for political writers: pamphleteers - the ill fancied bastard children of Voltaire, Thomas Paine and Orwell. Those that can make a difference are few and far between.

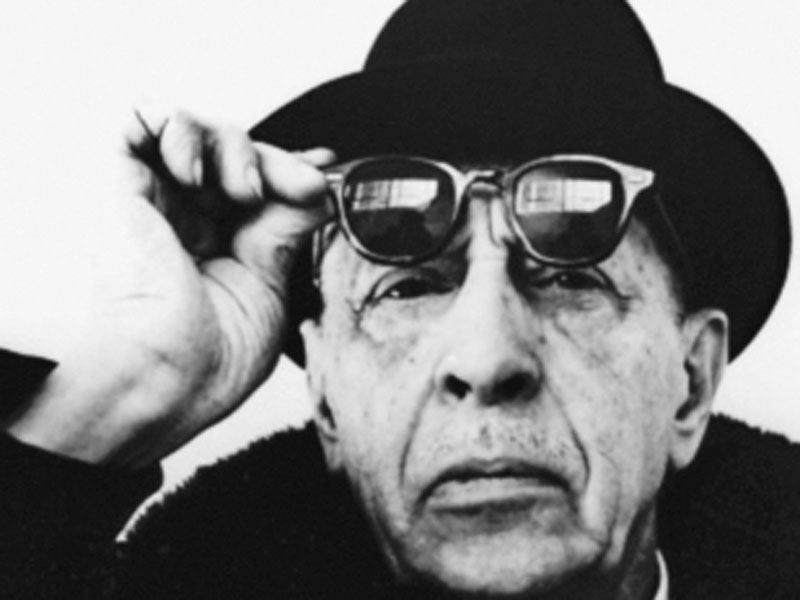

Christopher Hitchens was one such writer. For him, to write was a compulsion -an almost animal response to the world in all of it's joys, sufferings and inequities. At his best, Hitchens seemed able to meld tragedy, outrage and joy into a singular kinetic whole - a fire breathing prophet one moment, a demure coiner of witticism the next. The man could take complicated political, social or literary issues - score a cheap though frighteningly funny joke on the back of them - and make an often controversial point that forced one to come to recalibrate ones belief system. I certainly can't say that I agreed with him on everything, but Hitchens served as one of the architects of my intellectual foundation and I will remain indebted to him.

Hitchens liked to encourage the young, and clearly liked it better when one disagreed with him. The man clearly lived for intellectual debate and rarely lost. His skill at winning debates, and his ability to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat - even in those rare occasions where the facts seemed to stand against him probably earned him as many supporters as critics. Yet there he was, always there with a strikingly original one-liner and an opinion. Always an opinion.

I had the pleasure of meeting him twice. The first time was a drunken flurry of conversation and ideas - the man seemingly unfazed by mega doses of Johnny Walker as we, sitting on Monona terrace in Madison, Wisconsin one cold October afternoon managed to polish off the better part of a bottle of the stuff. The man was magnanimous with both his time and his whisky (although he did appear to drink most of the bottle with almost no debilitating effect whatsoever, while I was rapidly in my cups, so to speak). I still remember looking at him, even then, and thinking that he looked like he was made of some kind of parchment - the cigarette smoke and whisky clinging to his skin and infusing him with the essence of the pages of a book that he lived to turn. Despite the omni present booze and smokes, it was the love of the printed word that always was the most telling and that was perhaps his deepest addiction. Still he was no sedentary creature confined to a library - Hitchens was someone who exuded energy and who wrung from life everything it could give him and then some.

I met him again a couple of years later on a rainy night in Portland, he saw me in a crowd, astoundingly remembered me, served a refutation to the one point I felt I had bested him at years earlier and remarked how the dreary Portland rain overjoyed him because it reminded him of his boyhood in Portsmouth. Stubborn to the end, but stubborn with purpose. From all accounts, the man was not always lovely to deal with, and he proved unwilling to admit to any error of judgement when it came to Iraq. I will one-day have to write a longer essay about Hitchens' uneasy relationship with the Left, his flirtations with neo-conservatism and the rest. Despite this, even where I disagreed with Hitchens, I tended to respect his rationale for believing what he believed.

While his death seemed eminent for some time - very few people walk away from Stage IV Esophageal cancer (a malady which even if detected in it's early stages is often considered a death sentence) - Hitchens' death still feels like a shock. This may be because, for so long, he seemed to cheat the odds with his apetites for self destruction. Despite his diagnosis, part of me seemed to hold on to the belief that he would somehow cheat the odds and live to be 100 - if anything as an act of spite designed to give the incredulous a bloody nose. Sadly it was not to be. Wherever you are when you read this, raise a drink to Christopher Hitchens. The world will be a drearier, sadder and most importantly, a less interesting place as a result of his passing.

Christopher Hitchens was one such writer. For him, to write was a compulsion -an almost animal response to the world in all of it's joys, sufferings and inequities. At his best, Hitchens seemed able to meld tragedy, outrage and joy into a singular kinetic whole - a fire breathing prophet one moment, a demure coiner of witticism the next. The man could take complicated political, social or literary issues - score a cheap though frighteningly funny joke on the back of them - and make an often controversial point that forced one to come to recalibrate ones belief system. I certainly can't say that I agreed with him on everything, but Hitchens served as one of the architects of my intellectual foundation and I will remain indebted to him.

Hitchens liked to encourage the young, and clearly liked it better when one disagreed with him. The man clearly lived for intellectual debate and rarely lost. His skill at winning debates, and his ability to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat - even in those rare occasions where the facts seemed to stand against him probably earned him as many supporters as critics. Yet there he was, always there with a strikingly original one-liner and an opinion. Always an opinion.

I had the pleasure of meeting him twice. The first time was a drunken flurry of conversation and ideas - the man seemingly unfazed by mega doses of Johnny Walker as we, sitting on Monona terrace in Madison, Wisconsin one cold October afternoon managed to polish off the better part of a bottle of the stuff. The man was magnanimous with both his time and his whisky (although he did appear to drink most of the bottle with almost no debilitating effect whatsoever, while I was rapidly in my cups, so to speak). I still remember looking at him, even then, and thinking that he looked like he was made of some kind of parchment - the cigarette smoke and whisky clinging to his skin and infusing him with the essence of the pages of a book that he lived to turn. Despite the omni present booze and smokes, it was the love of the printed word that always was the most telling and that was perhaps his deepest addiction. Still he was no sedentary creature confined to a library - Hitchens was someone who exuded energy and who wrung from life everything it could give him and then some.

I met him again a couple of years later on a rainy night in Portland, he saw me in a crowd, astoundingly remembered me, served a refutation to the one point I felt I had bested him at years earlier and remarked how the dreary Portland rain overjoyed him because it reminded him of his boyhood in Portsmouth. Stubborn to the end, but stubborn with purpose. From all accounts, the man was not always lovely to deal with, and he proved unwilling to admit to any error of judgement when it came to Iraq. I will one-day have to write a longer essay about Hitchens' uneasy relationship with the Left, his flirtations with neo-conservatism and the rest. Despite this, even where I disagreed with Hitchens, I tended to respect his rationale for believing what he believed.

While his death seemed eminent for some time - very few people walk away from Stage IV Esophageal cancer (a malady which even if detected in it's early stages is often considered a death sentence) - Hitchens' death still feels like a shock. This may be because, for so long, he seemed to cheat the odds with his apetites for self destruction. Despite his diagnosis, part of me seemed to hold on to the belief that he would somehow cheat the odds and live to be 100 - if anything as an act of spite designed to give the incredulous a bloody nose. Sadly it was not to be. Wherever you are when you read this, raise a drink to Christopher Hitchens. The world will be a drearier, sadder and most importantly, a less interesting place as a result of his passing.